I've been working in games, whether it's on the media side or more directly in the industry, for quite a while now, and I've been a gamer for much longer. Having seen the rise of free-to-play and mobile games as well as getting to see the obsession with monetization in games firsthand, you'd think I'd be sure that microtransactions and lootboxes and all these new-age monetization strategies are not good for games. The thing is, though, that the problem actually feels a lot more complicated to me.

So, in this article, I'll walk you through why I'm not sure about microtransactions and give you a hopefully new perspective on why monetization in games is still in such a weird place.

Related: How Much Is Netflix a Month: Netflix Price Explained

Microtransactions in Other Mediums Outside Gaming

Imagine this: You walk into a movie theater, pay for your ticket, sit down, and you watch the movie. It's a great movie, too. Well-made, fun, and interesting. Just the right length, too. Finally, the credits start to roll, and you start getting your things together so you can leave.

But then, you get a notification on your phone. It's from the movie theater. It's thanking you for watching the movie, and it's telling you that you can, right now, pay a dollar to stick around after the credits and watch a specially-produced post-credits scene.

It's got all the same actors, it's written by the same writer, directed by the same guy, etcetera, but it's not part of the movie. It's just a cute little skit, a fun little original bonus piece of content. Money went into making it, and you can assume that you're going to like it, if you watch it.

Related: How Cryptocurrency and NFTs Could Actually Make Games Better

Is that bad? The instinct, I think, is to say yes. I'm not sure anybody wants microtransactions now in their dang movies. Just pay the ticket price and watch the movie. Don't overcomplicate it, right? That's fair enough, but it doesn't really make a lot of sense to be opposed to this on principle.

Bonus scenes, deleted scenes, bloopers, and all kinds of quirky extra content have been packaged into DVDs and special editions of movies, for a price, for decades. And considering all the Patreons and supporter subscriptions around, it's a pretty common practice to contribute a couple bucks to watch a well-produced piece of content, even if it's only a couple minutes long.

Nonetheless, nobody thinks movie microtransactions are a good idea. So, what's going on here? The problem is existential, I think. See, we all agree that art has value, and almost nobody thinks artists shouldn't be able to profit off their work, but the problem is that art is arbitrary. A certain piece of art doesn't have to have a certain set of components or be a certain length or anything else, so there's infinite room to chop up and sell art.

Related: Game's Aren't More Expensive Because of Inflation

Once 99-cent post-credit scenes become popular, why wouldn't you start seeing alternate endings being sold? What about sideplots you can get in your movie if you pay extra? If it all starts with a silly, fun thing that's cheap, does it end with choose-your-own-adventure movies with sky-high pricetags? This is the worry, and it doesn't necessarily have to do with any single sale.

Microtransactions in Games Have the Same Problems

Say you make a game. You release the game for a flat fee, and people love it. You make money, and you use that money to develop a big expansion to the game. Naturally, since fewer people will always play the expansion than play the base game, you make less money from the expansion.

However, people love the game, and they want more content, and there's more you want to do with the game. The problem is that the money just isn't coming in anymore, so either you've got to channel all your resources into a sequel or new project to keep your studio afloat, or you've got to figure out a way to make more money from the game you've already made.

Related: Here's Why Games Cost $70 Now, and It's Not What You Think

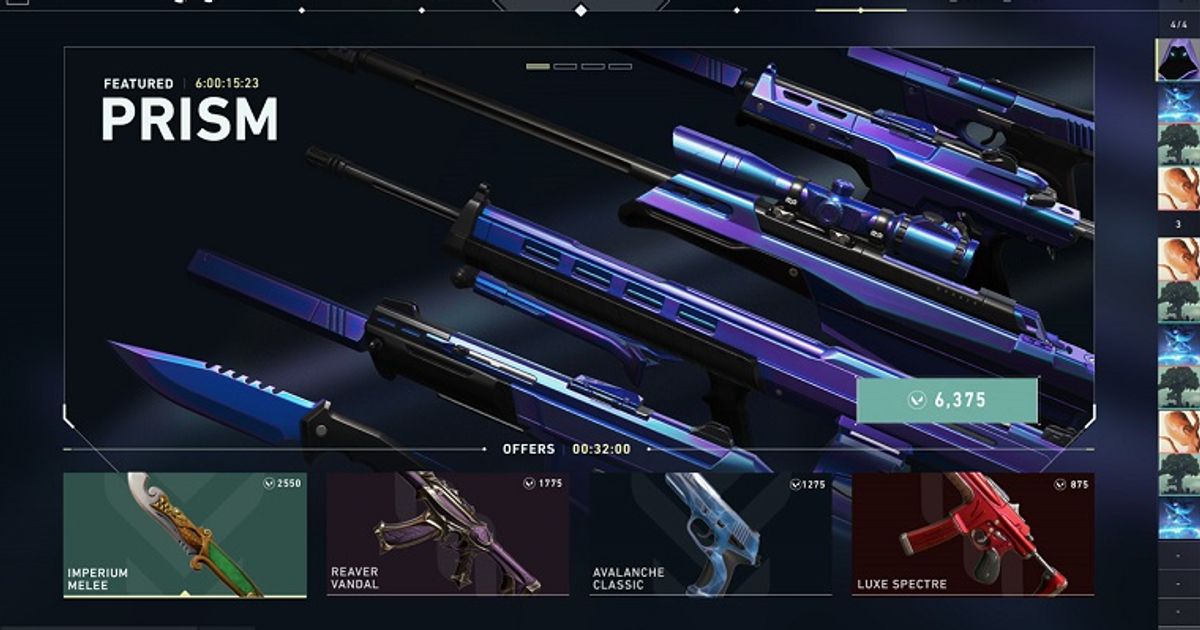

So, you decide to sell a $5 skin that just looks cool and does nothing else so supporters can help you fund more content for the game. Is that wrong? Maybe, but most people, I think, would say no. However, on the other side, what if you release a game that costs $60, fill it with expensive microtransactions, and you just take all the money it makes and give it to the executives as a bonus. Obviously, that sucks.

What's happening here is that the actual transactions aren't the problem, it's the extent and scope of them, and the natural inevitability is that once you start selling microtransactions, it quickly becomes impossible not to justify other microtransactions until you're suddenly the game filled with them that everybody hates.

And what's worse is that since the line between what's okay and what's not isn't always clear, you'll have this weird circumstance where gamers might hate microtransactions but still buy them anyways, which gives companies the signal that consumers think microtransactions are worth the price, so they put more in games, while gamers become angrier that more and more microtransactions are in games.

Related: Everybody Wants Microtransactions, You and Me Included

This might sound like the fault of the gamer, and sometimes it can be, but more often, microtransactions seem okay until suddenly they aren't, so it can be hard to pick a certain point where you think a microtransaction absolutely isn't okay. So, while a gamer might not like microtransactions but might be okay with a skin being sold to support development, what that looks like to a company is simply that gamers are willing to spend money for the content on offer, so why not offer more?

This vicious cycle leads to games being filled with microtransactions that might not individually be anything to be concerned about but at scale might be dystopian. It's a weird situation where the practice isn't wrong itself, but there's not really a good way to do it right. At least, that's what it feels like to me. What do you think?

Explore new topics and discover content that's right for you!