Modern anime and manga is typically broken up by rough target demographics. Two major examples of this are shonen and shoujo. Shoujo manga is manga aimed at teenage girls (Examples include: Sailor Moon, Fruits Basket, Yona of the Dawn) and shonen is manga aimed at teenage boys (Dragonball Z, Naruto, Fullmetal Alchemist). Of course, women of all ages also enjoy shonen and men of all ages can enjoy shoujo. This categorization is simply based on the main demographic the manga is aimed at and the types of magazines the manga runs in.

Shoujo manga is mainly associated with romance in the minds of many, but it actually encompasses a huge variety of genres and artistic styles. Sci-fi, fantasy, action, slice-of-life- all can be found in shoujo manga. The same rule applies to shonen.

Yet, like many things aimed at girls, I’ve seen shoujo manga denigrated and dismissed as lesser. Back when I was in college, I attended an anime club. We would mainly watch shonen anime, which I didn’t mind. I like a lot of shonen, as do many women. There are a lot of great shonen by women, contrary to popular belief. But there’s also a lot of stuff I like that’s catergorized as shoujo. It’s every bit as exciting, action packed and thought provoking as shonen manga.

Revolutionary Girl Utena

I started bringing some shoujo I though was appealing in that respect, like Revolutionary Girl Utena, into the club and was met with some disdain and resistance, especially from some of the more macho guys. One guy claimed that there wasn’t any shoujo about flying and space (very untrue) and another one said “shoujo doesn’t have much action”. They assumed because this was “for girls” there was nothing to appeal to them. I was expected to be able to sit through and enjoy something aimed at boys, but it was unthinkable they would ever do the reverse.

I’ve seen some similar dismissive sentiments on shoujo on the internet groups, dismissing it as all being toxic romance or as not ever having strong and dynamic female leads, etc. I even went to a panel that was supposedly about “feminism and anime”, where the panel leader claimed there were very few female manga artists. This is patently untrue if you consider that in addition to the women writing shonen, there’s huge amount of shoujo manga and the most of it is by women (and then there’s josei and seinen but I digress). It upset me to see these women dismissed.

This prompted me to do some research into the history of shoujo and subsequently, I discovered how powerful and influential shoujo manga really is. The group of women who revoltionized shoujo also revolutionized manga as a whole, making a huge impact at manga aimed at all demographics. We owe much of modern manga to them. Moreover, the manga were hugely important in how they subverted societal expectations and examined gender and sexuality. I thought I’d share what I’d learned.

Be aware this is just a rough outline of a very dense and complicated history. My goal with this article is mainly to get the word out there about this, so this is by no means an exhaustive examination. I’ve included several sources at the bottom of the page you can check out if you want additional information. With that said, let’s take a quick look at the early history of shoujo and the group of women who rocked the boat!

Princess Knight

A sort of predecessor of shoujo manga existed pre-World War II in that there were (often single panel) comedy cartoons featured in Japanese magazines for girls. However, many consider the starting point of shoujo manga to have happened post-war with Osamu Tezuka’s Princess Knight. Tezuka, often called the father of manga, created one of the earliest story-driven manga aimed at girls with this tale of a princess who pretends to be a boy so she can inherit her throne. These themes of crossdressing and gender exploration would be seen in a lot of later shoujo works, like The Rose of the Versailles and Revolutionary Girl Utena.

However, girls’ comics were initially seen as lesser even by those who made them. It was mostly men who wrote shoujo manga at that time and many of those artists considered it something for “rookies” to work on until they got the opportunity to move over to shonen. Academics ignored it. Manga critic Ishiko Junzo admitted shoujo was considered “sub-par” compared to shonen and was “barely researched" at this time.

There were at least a few notable female artists in that era. One of particular note Hideko Mizuno, whose biking-and-rock-music manga Fire! contained the first sex scene ever in a shoujo and inspired many later artists. But men still largely dominated shoujo.

Graphic representing various artists in the Year 24 Group. Taken for here.

That all changed in the 1970s, thanks to a group of female artists that revolutionized shoujo and had a huge impact on manga at large. This group of artists was called “The Year 24 group” or the “the 49ers” since most of them were born around 1949, the 24th year of the Japanese Showa era. They transformed shoujo into a medium dominated by men to one dominated by women. Interestingly, this shift also coincided with shoujo gaining mainstream popularity and respectability and academic articles being written about it. (Who could have guessed that artists treating stories for girls like a serious endeavor rather than lesser work that’s practice for “real manga” would make people more interested in them? Shocking!)

Shoujo manga had primarily focused on innocent pre-teen girls in fantastical settings, but the Year 24 group’s comic dipped into more mature themes. This included in-depth exploration of gender and sexuality (including gay relationships), exploration of mental illness and suicide and coming-of-age stories. Rather than preteens, glamorous teenagers became the more common protagonists. The subject matter was incredibly varied, ranging from sci-fi to historical drama to sports stories.

These women didn’t only experiment with subject matter, but artistically as well. These artists shirked the comic conventions of the time. Ignoring the “rows of similarly sized rectangles” layout that was the strandard at the time, they would vary panel size, configuration and shape to convey dramatic emotion and action, going so far as to remove panel borders at time. This experimentation in composition paved the way for the more artistic layouts in modern manga of all genres and demographics.

They Were Eleven

One of the most influential artists from this group was Moto Hagio. Her work included sci-fi stories like They Were Eleven, which told the story of a group of teenagers trapped together on a decommissioned spaceship as a “test” and A, A Prime, about a futuristic universe where a humanoid race called “Unicorns” was genetically engineered for space travel. Gender identity and sexuality were explored through the lens of sci-fi in these works, which feature sex changes and intersex characters. The works are cited as a forerunner to both shoujo and shonen with gender-bending elements like Ranma ½ and also inspired other sci-fi manga like Urusei Yatsura.

Hagio wrote stories in all kinds of genres- other notable works were the historical fantasy about a family of vampires, The Poe Family, and the “boys love” story The Heart of Thomas. It was the Year 49 group that gave birth to the boy’s love genre in manga. They openly depicted relationships between men (though they were pretty much always tragic). Keiko Takemiya, a 49er who was also one of the first women to write shonen manga with her influential sci-fi Toward the Terra, published what is thought to be one of the first boys' love works, In the Sunroom. It featured the first male-male kiss in manga.

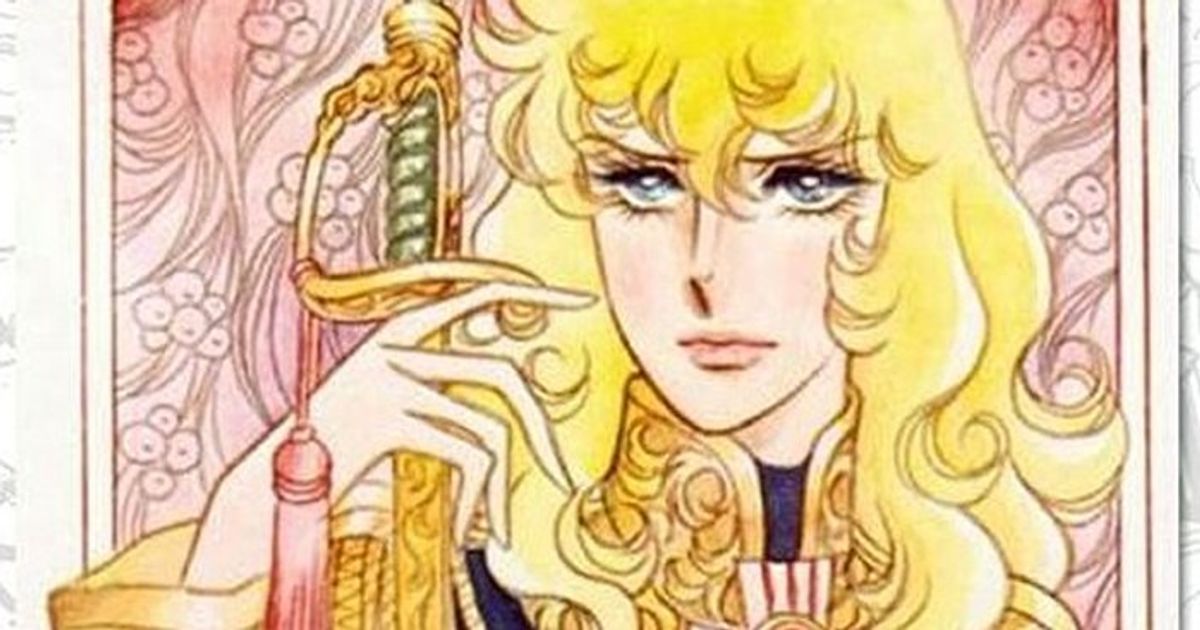

The Rose of Versailles

“Girls' love” manga (exploring romantic love between women) also owes its roots to the Year 24 group. Ryoko Ikeda was a big part of what propelled shoujo manga to mainstream popularity with her wildly popular The Rose of Versailles (which received stage adaptation, a movie and is still commonly referenced in manga to this day). This manga starred a crossdressing bodyguard to Marie Antoinette named Oscar, who was a “woman raised as a man”. It was an action-packed swordfighting manga set around the time of the French Revolution. It explored gender identity, gender roles, class differences and love between women- several women in the manga were depicted as being in love with Oscar, including the reoccurring character Rosalie. Erica Freidman credits this manga and Ikeda's other work, Dear Brother, with truly introducing themes of romantic love between women to manga.

Other notable works from this group include From Eroica with Love by Yasuko Aoike (a comic take on spy stories), the historical drama Emporer of the Land of the Rising Sun by Iyoko Yamagishi and the tennis manga Aim for the Ace by Sumika Yamamoto.

As you can see, the shoujo has genre spanning influence and innovation. An overview of important sci-fi, fantasy and action manga that doesn’t include the works from the Year 24 group is incomplete. These manga included every flavor of story, explored taboo subjects and the psychology and agency of women in a way that was unprecendented and also contained many artistic innovations.

Please Save My Earth

And this exploration continues into modern shoujo manga. There was a lot of innovative sci-fi manga in the 90s, like Please Save my Earth by Saki Hiwatari (about teenagers who remember their past lives as alien scientists) and Moon Child by Reiko Shimuzu (which explores cloning). Professor Yukari Fujimoto noted that shoujo manga from this era focused a lot female self-fulfillment, citing the popular action-based shoujo stories Red River, Basara, Magic Knight Rayearth and Sailor Moon as stories about “girls fighting to protect the destiny of their community”. She also noted the emphasis these manga have on the importance of bonds between women. She felt these stories symbolized the dawn of a female fighter that was “independently developed apart from shonen manga”.

If you’d like to take a look at some of these action-packed tales with dynamic, compelling female leads, check out my article recommending a few shoujo manga in that vein.

I hope this article helps to shed some light on the rich history and artistic importance of shoujo manga. It can’t be pigeonholed into a single genre or stereotype and anyone can find something that appeals to them in the vast amount of stories out there. (There’s even a lot of gory shoujo horror comics out there) If you like any type of anime or manga, it’s important to respect shoujo.

To learn more about shoujo manga and the year 24 group, please check out these sources:

Spotlight: The History of Shoujo Manga

The Power of Girls Comics: The Power and Contribution to Visual Culture and Society

10-Minute Shoujo History Lesson

Say It With Manga: Year 24 Group Edition

(PDF Download) Japanese Contemporary Manga: Shojo

Explore new topics and discover content that's right for you!

Fandoms